ICFPC 2024

Note: This write-up was migrated from my GitHub repo with a few small tweaks. You can check out the original here. It's mostly filler for this site, but it's also special because it's the first long write-up I've posted publicly.

About the team

The team consisted of 4 members:

- SanguineChameleon

- SanguineChameleon

- SanguineChameleon

- and last but not least, SanguineChameleon

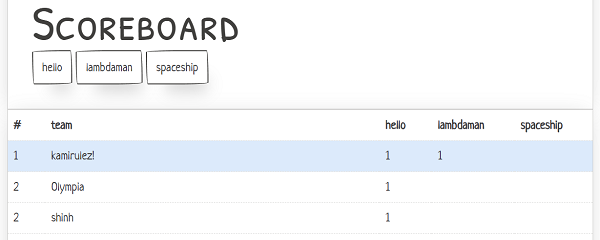

At the end of the contest, we I was ranked #31 overall.

Prologue

At the time of writing this, it's been 2(ish) days since the contest ended. I don't remember everything exactly (it was a hectic 72 hours!), so I'll only be summarizing what I did.

This write-up assumes you're already familiar with the tasks, so if you haven't already, please check out the contest website and the official solutions first.

Writing the Interpreter

I've written a few interpreters/compilers for languages like this before, so this wasn't too difficult. That is, until I had to deal with the B$ token.

This was the International Conference of Functional Programming Contest after all, so in hindsight, I should've done research about lambda calculus before the contest. Oh well.

Using Python's lambda expressions on their own didn't work, because Python doesn't use lazy evaluation like Haskell, so it might end up expanding a formula infinitely many times. And I don't know Haskell, so my only choice was to implement it myself.

I probably didn't do it correctly, as the number of beta reductions my program used did not match with what they gave in the example. But hey, it still works, and that's good enough.

The contest started at 7 pm for me, and after screaming and crying for a while, I managed to get the interpreter working at around 6 am the next day, and got some well-needed sleep.

Controlling Lambda-Man

For some reason I didn't internally register the fact that Lambda-Man was allowed to run into walls, so I made this a lot harder for myself.

Let's assume we're not allowed to compress the path in any way. How would we visit each cell at least once using the fewest number of moves?

Here's my (probably not that great) idea: Let's take an arbitary spanning tree of the grid graph. We'll only be traversing the edges of this tree. Consider the last node we end up on. Then every edge that doesn't belong to the path from the root to this node must be traversed twice. So to minimize the number of edges that get traversed twice, we want to maximize the length of the path from the root to the ending node.

Now we can forget about finding a spanning tree and instead focus on finding the longest simple path starting from a given cell. I used beam search for this. Each state consists of the set of visited cells and the current cell. States are ordered based on the number of unvisited cells that the current cell can reach, with more cells being better.

This approach was reasonably good, so I decided to move on to the other tasks as they seemed more interesting.

Near the end of the contest, I shortened some of the solutions by compressing the paths into a base 4 integer. Of course, they were still much longer than simple random walks. I also solved a few test cases by hand.

Controlling the Spaceship

This is just a plain old heuristics problem, and I still suck at those. Whoops.

I used hill climbing on the visit order of the points. To transition from one state to another, I picked two random points and swapped them.

How do we get from one point to another? Let's do it in a greedy fashion. We'll deal with each axis separately.

Suppose it takes K moves to get from point A to point B. Then the first acceleration dx1 will contribute a distance of dx1 * K, the 2nd acceleration dx2 will contribute a distance of dx2 * (K - 1), and so on. It's sort of like prefix sums.

So for a given number K, we can calculate the minimum and maximum possible distance that can be traveled (making sure to offset everything by vx * K, where vx is the current velocity). Then we can iterate through the values of K and find the smallest one that works.

(I realize that this can probably be done in O(1) by solving a quadratic equation, but unfortunately, I've forgotten the quadratic formula.)

You may notice that my code looks more like simulated annealing without the temperature and acceptance probability function. This is because I was too lazy to actually implement it, and my laptop was threatening to blow up.

Controlling Time and Space

3D was easily the best task of the contest. For some reason, I really like solving problems in weird esoteric languages, despite how headache-inducing they might be.

I wrote an interpreter for the 3D language, and I edited the programs in a standard text editor and tested them manually. Nothing special, really, though I think using something like a spreadsheet would've been much less painful than a text editor, where you can't shift things that easily. But I like to give myself a challenge.

The time warp acts as a wonky goto statement that can only jump backward, and once you get your head around that, it's not too difficult to write programs in this language, but it might get a bit tedious.

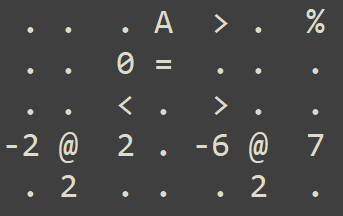

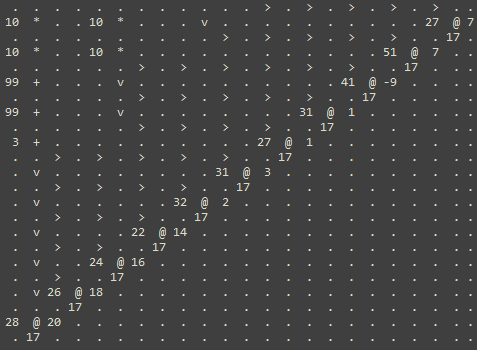

The only "innovation" (if you can call it that) I had for this task was this locking mechanism, that allows you to teleport values once and once only:

In the above example, once the value of A equals 0, the equality operator gets triggered, which causes the 0 to move into the position of two time-warps. One of the time-warps sends the 0 somewhere else, and the other one overrides the = sign, which prevents the program from entering an infinite loop.

I used variants of this mechanism a lot in the later, more complex problems. There's probably a much more intelligent way of doing this, but I came up with this myself, and I'm happy with that.

I won't bore you with the details, so here's a quick rundown of my approach for each problem:

-

Problem 1: Just implement a for-loop.

-

Problem 2: Have one loop repeatedly add

1to the value ofAand one loop repeatedly subtract1from the value ofA. The one that finishes first determines the sign and absolute value ofA. -

Problem 3: Same idea as problem 2.

-

Problem 4: Same idea as problem 2. This time we're using the value of

A - B. -

Problem 5: Calculate the GCD of

AandBusing the Euclidean algorithm, then calculate the LCM from there. -

Problem 6: Again, a "simple" for-loop.

-

Problem 7: We can extract the digits of

Aone by one by repeatedly dividingAby10. Then, we can construct a new number from left to right using these digits. Since we've extracted the digits ofAfrom right to left, the new number we've constructed is actually the reverse ofA. Now we just check if these two numbers match. -

Problem 8: Same as problem 7, but iterate through the bases one by one.

-

Problem 9: Extract the digits of

Afrom right to left. Usually, you'd check a bracket sequence is balanced by iterating through the symbols from left to right, but it actually still works if you do it from right to left. Just treat closing brackets as opening brackets and vice versa. To check if a bracket sequence is balanced, maintain a sums, wheresincreases by1for every closing bracket, andsdecreases by1for every opening bracket. The value ofsmust never become negative, and by the end, the value ofsmust be exactly0. -

Problem 10: Same idea as problem 9, but because there are now two types of brackets, we need a stack. We can maintain a number

tthat represents the stack. Every time we add something to the stack, we add a digit to the end oft, and every time we pop something from the stack, we remove the last digit oft. -

Problem 11: Because Lambda-Man moves no more than

100times, we can put them in the center of a201by201grid to ensure that they don't leave the boundaries of the grid. Then, we can represent each cell in the grid as a number from1to40401. We'll maintain a numberpthat represents the list of cells in the grid that Lambda-Man has visited. Because of the small constraints, for each iteration, we can naively check if the current cell has appeared inpbefore inO(N). You'll have to compute some of the constants during the program runtime, as some of them are larger than the limit of99(this was quite annoying). -

Problem 12: I didn't actually use Horner's method for this, I just computed the Taylor series sum as you normally would, from left to right. I just maintained the values of the exponents of

xto40or so digits. Make sure that after multiplying the current exponent byx^2, you divide the result by10^80. I definitely did not waste another hour fixing that…

Whew! That was a lot to unpack, but it was really fun to solve everything.

Unfortunately, due to my lack of code golfing skills, I didn't rank too high on this task despite having solved all of the problems. I would've preferred to have teams ranked by the number of problems they solved like for Efficiency, because solving the problems themselves was already challenging enough as it is…

Building a Quantum Computer

I also enjoyed solving Efficiency as well. I find it quite interesting that humans can still reason about programs that won't terminate before the end of the universe.

I won't go through the solutions here. You can read the official solutions for yourself if you'd like. This task is simply just an enjoyable series of puzzles.

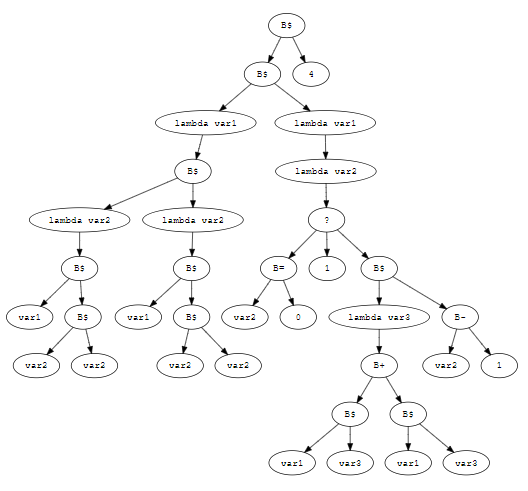

I solved all of the tests by hand, except for test 1, which I was able to successfully evaluate with my interpreter (hooray!). Originally I drew the parse trees on paper, but I quickly realized that it would become infeasible for the later tests, so I made my own visualizer using Graphviz:

Epilogue

I'd like to thank the ICFPC 2024 organizers for such an amazing contest!

I destroyed my sleep schedule for this, but it was very well worth it. Before the contest started, I thought it'd just be a simple heuristics challenge. I didn't expect it to be this complex, and it was so much fun!

I had a lot of great moments in this contest, but the best moment of all, in my opinion…

Was when I was in 1st place for like 5 minutes.

And that's a wrap! Thank you for reading :3